One of my most difficult days teaching college anthropology happened in the spring of 2017. We were discussing political systems. Tensions were high. Two students, one liberal, one conservative, stood up and started screaming at one another in the middle of class. I had to take both outside, separate them, and deescalate. Classrooms were growing increasingly contentious, a reflection of the escalating political climate of the United States.

In the fall of 2019 I wrote the article, 17 Things I Have Learned Teaching Anthropology and Cultural Diversity. If you haven’t stumbled on it before, it’s about insights I gained in my early days of lecturing. In this difficult political climate, I knew that these conversations about diversity and culture were more important than ever. So, after that shouting match in 2017, I began experimenting with different methods to teach anthropology and diversity.

As I was writing that article in 2019, I discussed how contentious the classroom had become with my soon to be co-author, Kyra Wellstrom. Both of us had been teaching anthropology for more than five years at that point, and had seen firsthand the changes in our classrooms with each passing semester.

Rethinking Worldbuilding

It wasn’t just the classrooms Kyra and I discussed. Both of us were frustrated with the inaccurate worldbuilding in fiction, films, and games. There were two books contributing to this problem, Sapiens and Guns, Germs, and Steel. Anthropologists have debunked both books, though they remain popular. Both sell an overly simplistic narrative about culture and history that doesn’t hold up to any real scrutiny.

Why did we care so much? Well, what we imagine matters. If your culture is constantly creating stories based on inaccurate information and stereotypes, that becomes part of the public consciousness. So, bad worldbuilding can actually reinforce biases and in some cases, bigotry. On the other end of the spectrum, good worldbuilding can help people have greater empathy, source possible solutions to real-world problems, and deconstruct stereotypes. Fictional settings are ideal for playing with ideas, especially if you’re a creative.

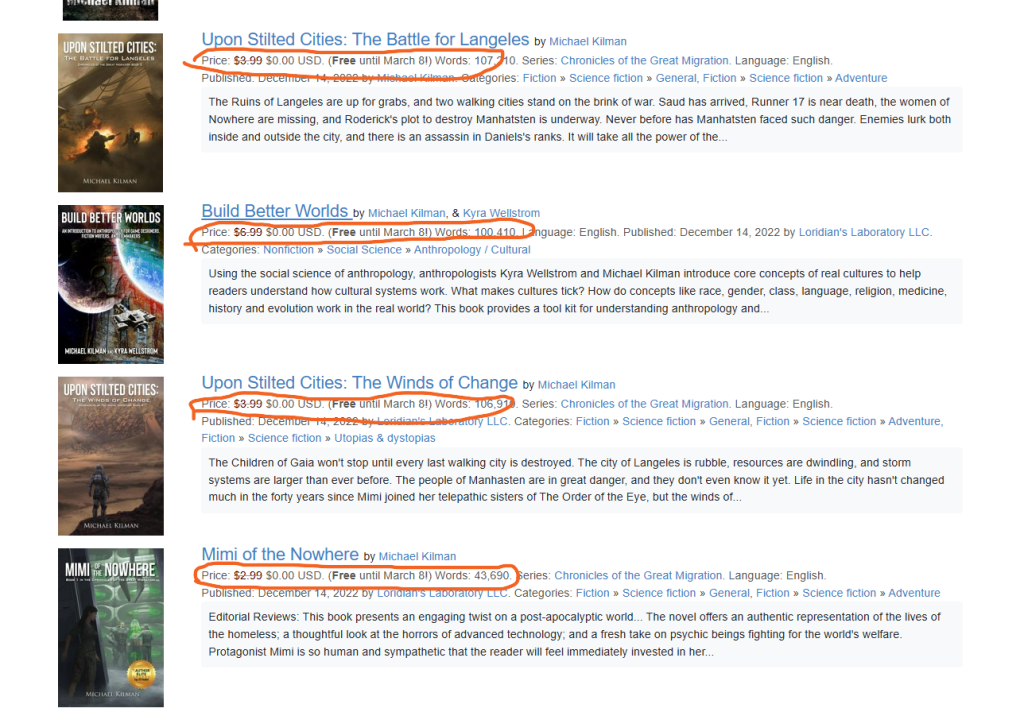

So, that fall, as I was writing the 17 things article, Kyra and I decided to write a book on how to use anthropology to worldbuild. That book, of course, became Build Better Worlds: An Introduction to Anthropology for Game Designers, Fiction Writers, and Filmmakers.

As we began writing the book, we realized we could potentially help solve two problems at the same time. By writing an accessible text on anthropology for worldbuilding, we could help people write more accurate and immersive fiction. We also realized that we could use the book in our classrooms to approach contentious topics from a different direction.

Each of us took the model and experimented with it in different ways.

I tried several experiments in my classroom. The first was to have individuals build their own worlds. And while students seemed to enjoy this approach, it did nothing to address the tension in this classroom. If anything, students doubled down on their opinions. I quickly realized that having individual students do their own projects, isolated them from others. Unfortunately this further entrenched them in their own worldviews which was the opposite of my goal. It’s easy to become myopic when you’re in your own head.

What Changed Everything

After two semesters and some student surveys, I took a different approach. This time I tried group worldbuilding.

It changed everything.

Each student was assigned to a group of 3-5 people, and through three key projects throughout the term, they built fictional worlds together. Their final assignment was to present their fictional world creatively to teach the entire class. I encouraged them to use their own backgrounds, knowledge, and skills in their projects.

There were so many brilliant final projects. Some did plays (in full costumes), created videos, and built tabletop or board games. We had mock news reports and political campaigns, hilarious tourism brochures, original music, languages, recipes and so much more. Finals week became a space of play instead of stress.

While, no model is perfect, and there are some students who hate group work, it completely changed the conversations in class. Since I began the worldbuilding approach, I’ve never had another shouting match in my classroom. Instead, more students showed up to class ready to discuss. They understood that our in-class content and conversations helped them improve their fictional worlds. Instead of viewing a classmate with a different opinion as a challenge, suddenly their differences were fuel for building a more nuanced and holistic fictional world.

In these projects, they were practicing compromise and gaining experience finding common ground to work toward a mutual goal. They were rehearsing democracy, a skill we must always practice if we are to keep it.

But it wasn’t always easy. That’s kind of the point. Some groups had problems working together. One group project was derailed by a the collapse of a romantic relationship, and I had to work with the students to find a way to resolve things. Sometimes things didn’t get resolved, and a student dropped the class. Classrooms shouldn’t be uniform and tidy things. If they were, how could anyone learn? This whole human thing we do is complicated. That’s what anthropology is all about: trying to understand the complexity of the human experience.

Moving Beyond the Classroom

The success of this approach led to my 2021 Ted Talk, Anthropology, Our Imagination, and Understanding Difference. Then, after presenting at the Society for Applied Anthropology annual conference in 2022, I had several inquiries to write an academic article on the subject. Ultimately, I wrote a book chapter for an academic book detailing my model. The chapter was titled: Worldbuilding as Pedagogy: Teaching Anthropology and Diversity in Contentious Classrooms. That chapter came out in the summer of 2025.

The last 12 years, since I first began teaching, I’ve learned as much, if not more, than in all my coursework and field research in graduate school.

Watching our country lean more and more toward authoritarianism and away from democracy in the last decade, it’s been my classroom that’s given me hope. Because I saw firsthand that how you approach these contentious issues is almost as important as the topic itself. I’ve learned that no matter how difficult the discussion is, there is a way to get most people to learn to see humanity in one another.

If I were to add anything to my old 17 Things article, it would be this: You cannot find meaning out in the world, you have to create it. Sure, you can always let other people create meaning for you, but if you do that, you’ll be stuck in a life that’s not your own. If we want to build a better world for our descendants, if we want to be good ancestors to future generations, then we have to create meaning together to build a better world.

Are you experimenting with worldbuilding, pedagogy, or collaborative learning in your own work? I’m always interested in learning about different approaches or helping others to actualize theirs. Feel free to reach out with your thoughts or questions. I also occasionally host worldbuilding Q&A sessions over on YouTube for creatives.